"What can we do without water?"

|

A very few years ago while living in Malawi, I helped to design a community hygiene education program in a remote northern region called Nthalire. The idea was to dispatch Community Educators for several months to various schools to train teachers, government extension workers and community members in basic hygiene information and practices: hand washing, proper latrine use, how diseases are spread, drinking water purification, and proper food storage.

Nthalire is not easy to reach. To get there, you drive up the paved highway from Lilongwe for about 5 hours. Then you veer off onto a dirt road that climbs steeply up towards the Nyika Plateau, a high grassland that is one of the least populated places in Malawi. Nearing the top of Nyika, the road deteriorates, with giant potholes and crevasses that require a four-wheel drive and a very careful driver. Once across the plateau, the road plunges down the other side, eventually snaking into Nthalire area.

On the way down, a breathtaking landscape rolls by: hundred-meter waterfalls, tree-lined hills rolled out like carpets, and the still African sky. As we finally pulled into Nthalire near sunset, relieved and dusty, there was not much more to disturb the air than a few chickens squawking, women singing, and kids laughing as they kicked around a ball made from plastic bags. Thatched huts dotted the area, and as our car kicked up dirt through “town,” we could see a couple of vendors, selling cooking oil and salt, lighting their kerosene lamps in the hopes of an evening sale.

That night, I remember, the sunset was spectacular, throwing red and yellow fire across the plateau from which we had just descended. And as I sat on the front step, I thought about how little, and at the same time how much, the world gives to her inhabitants. And about how much, and how little, as people we can do to make any difference.

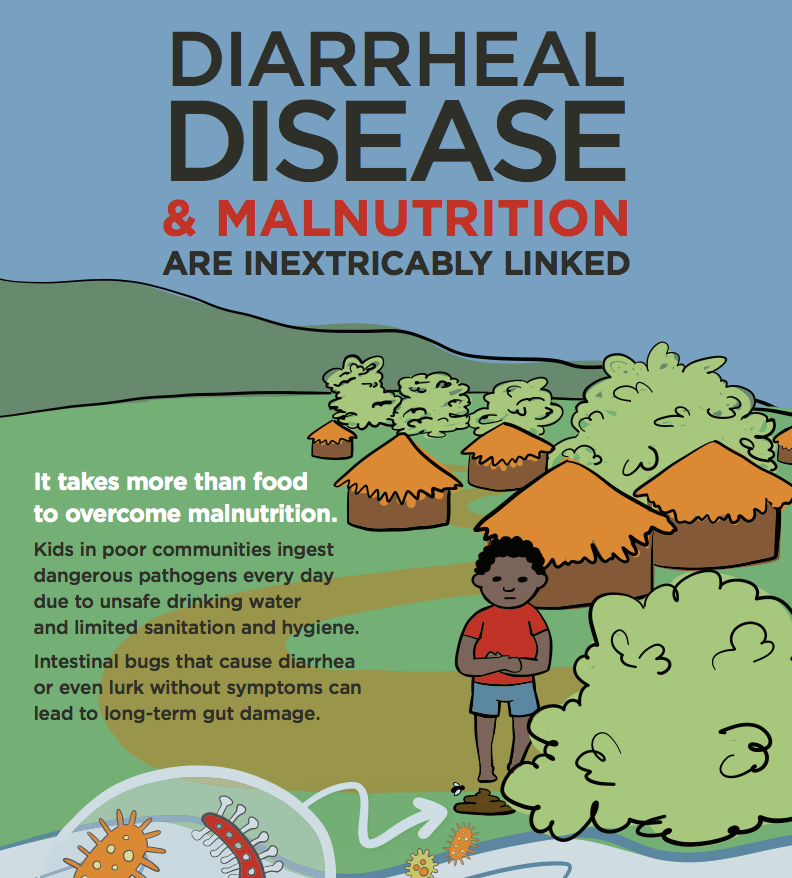

In Nthalire, we visited schools and talked to headmasters and students, teachers and parents. It's amazing how resilient people can be, even in the face of an appalling lack of basic human needs like water. At the same time it's amazing how confined they are without those fundamental things. Their universe remains small, because everything depends upon a source of water. People can't take baths, they can't wash their clothes. They can't clean the pit latrine or their babies' bottoms. Water, whatever its quality, is a precious commodity - to be planned for, waited for, fought for, and worked for.

And then it must be rationed out to drink - in small, sporadic amounts. Children skip school to fetch it. Sick mothers lug heavy buckets on their heads and babies on their backs to get it. Headmasters shrug their shoulders at low school attendance, pupils itching at scabies, and students clutching their stomachs from diarrhea. “What can we do,” they asked us, “without water?”

But still, people laugh. One of my favorite moments of that trip happened one early morning during a visit at Therere Primary School. Walking back to our car after meeting the headmaster and the village chief, we accumulated an entourage of about 200 kids, all of whom wanted to look at us, to touch us, to wave, and to practice their few English phrases. “Momma!” they would call. I'd turn around, and the whole crowd would shriek with laughter. “Dadda!” they would call, and when we would turn around, the same reaction again.

Finally, after thanking our hosts, we got into the car and began to wave goodbye. As we did the kids began to wave wildly: “Good night!” they screamed, jumping up and down. “Good night!” as we drove out onto the road into the early morning air. “Good night!”

In Washington DC, we feel worlds away from those kids in Malawi, and we are. But we all share the same world - and we ought to share the same human rights. With increased commitment from the US government and global donors to help provide safe water and sanitation, thousands of children in Nthalire, and places like it, will have a greater chance at health, dignity, and opportunity.