Cambodia: from policy to practice

|

Summer 2006, rural China: My colleagues and I take a bathroom break at a rest stop on the side of the road on our way to a health clinic. Unlike many female restrooms around the world, there isn't a long line of patrons waiting to use the holes in the ground separated by slabs of cement. I walk over to one of the farthest holes in the room and, my colleague stands in front of my “stall” as a human door. Other patrons giggle at how shy we are using the makeshift toilets. I strategically place my feet as far away as possible from the urine and feces on the ground, remnants from previous guests who had missed their chance to score inside the basket of waste collecting beneath the building.

Summer 2006, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: I am out in the countryside conducting a site visit. I really have to use the restroom. When I ask where the toilet is located, one of the locals points to an outhouse in the middle of the field and says something in Mongolian for my colleague to translate. “He is embarrassed for you to use the outhouse,” my colleague tells me. “He says it smells very bad and thinks it is better if you hold it until you get to your hotel.”

Fall 2010, Kampong Thom province, Cambodia: We're observing a village health volunteer train a group of mothers on diarrhea and pneumonia. After the training, I ask her how she thinks it went. She tells me that even if we train the mothers on how to prevent diarrhea and pneumonia, they lack basic, critical supplies like soap, water filters, and latrines.

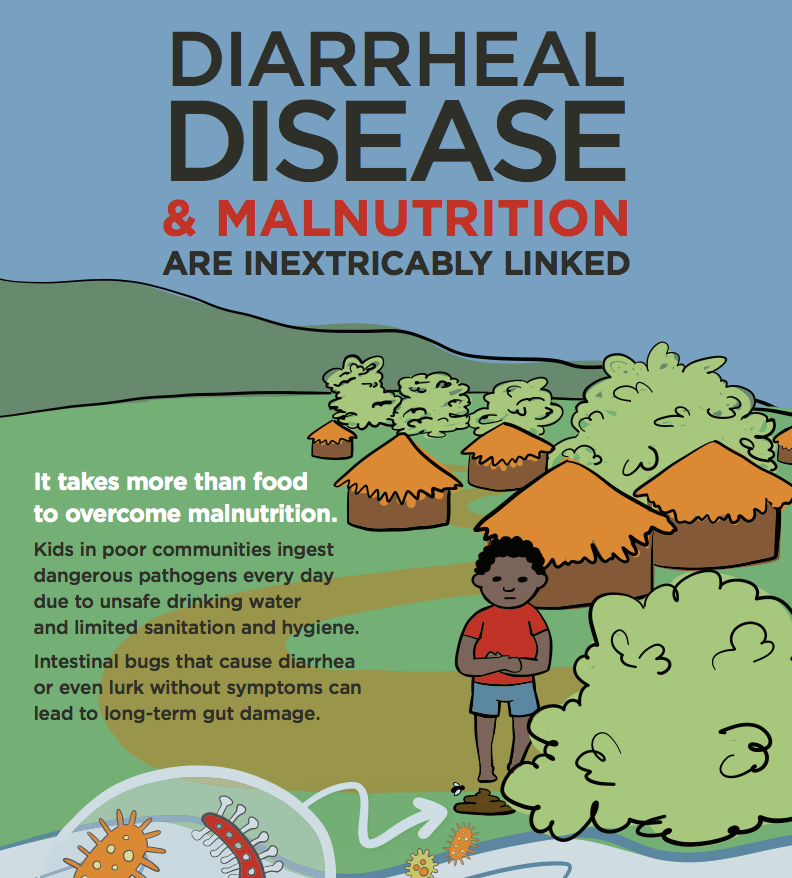

I have encountered challenging situations when having to use the restroom. Factors beyond my control: no toilet paper, no soap, no water, non-flush toilets; things I took for granted at home, at work, and even at most of the shopping malls back home in Utah. When I started to work on the diarrhea and pneumonia project with the PATH team in Cambodia, I learned first-hand how uncontrollable factors such as flooding, dirty water, and poor sanitation contribute to high rates of diarrhea.

My favorite health theory is the ecological model, which explores how environments influence health behaviors and thus health outcomes. My previous post raised the question of how health policies and behavior changes are linked in order to work with one's environmental context. In order to gain a better understanding, I spoke to members of the Technical Working Group for Acute Respiratory Infection and Diarrhea Prevention and Control, who are helping revive programming to address childhood diarrheal disease and pneumonia in Cambodia and are providing guidance on key policies:

-- Mr. Ork Vichit, Program Officer for childhood pneumonia and diarrheal disease at PATH

-- Mr. Chum Aun, Health Officer for maternal and child health issues at UNICEF

-- Dr. Chhorn Veasna, Program Manager of the National Program on ARI and Diarrheal Disease at the Ministry of Health in Cambodia

-- Dr. Bun Sreng, Chief of Bureau of Prevention and Control for the Department of Communicable Disease Control at the Ministry of Health of Cambodia

How did the experience of local health staff inform the revision of the national policy on pneumonia and diarrheal disease?

Mr. Vichit: The new policy focuses on community participation. If we want to strengthen the community level, we have to strengthen all health levels: national, provincial, operational, and health center levels in order to properly prevent, manage, and treat diarrhea and pneumonia. For instance, equipping village health volunteers (VHVs) with ORS and zinc was a key piece of the revised policy, which we incorporated based on community feedback.

Mr. Aun: This is the country's first policy allowing VHVs to administer ORS and zinc. With VHVs being able to provide direct treatment to mild cases, they can prevent severe cases.

Low-osmolarity ORS and zinc are now pivotal parts of diarrhea treatment and prevention in Cambodian clinics.

How important is it that national and local level efforts coincide to prevent and treat diarrhea and pneumonia in Cambodia?

Dr. Veasna: [Because of this pilot] VHVs have now been specifically trained on diarrhea and pneumonia. They are better connected with the National Program and moving forward can bring together national and local-level efforts. This connection is important as we try to have a more coordinated strategy.

Now that the policy has been revised and approved, what needs to happen in order for the changes to take place?

Mr. Aun: Widespread dissemination of the new policy must take place as fast as possible. The accompanying national guidelines should also indicate how health center staff will work with VHVs in ensuring that ORS and zinc are being properly administered in the villages. In addition, the guidelines must also indicate how health center staff will coordinate with VHVs to make sure that they have adequate supplies of ORS and zinc is continuously replenished. Interpersonal communication between VHVs and caretakers of children under five is essential to the success of new programming efforts by the National Program. Furthermore, VHVs must continually be trained on the most updated information on prevention and treatment, made aware of changes in policy, and must communicate this information to caretakers. Residents in rural Cambodia do not have access to mass media such as television and radio, and so VHVs are crucial to linking them with information.

Dr. Sreng: Families, especially the poor in Cambodia, have many things to worry about including making a living and finding food for their children. We need to communicate effectively to them that if they take care of their children by keeping them clean and preventing them from getting sick, they will save money by spending only five cents for a bar of soap instead of $25 (US) to treat severe diarrhea if they were to seek care from a private health care provider.

A Village Health Volunteer educates a mothers' group in her community.

How do you link policy and behavior change initiatives in an environment where there is a lack of basic resources such as latrines and water filters in order to prevent children from getting sick?

Dr. Veasna: The National Program must continue to work with key stakeholders like PATH and other government arms to fill gaps such as the lack of access to these life-saving supplies. PATH's work with water filters is a good example of how we can ensure access to populations in need. What has made this pilot successful is the collaborative effort from stakeholders in all areas. These partnerships are important to support the National Program's core work: helping to decrease morbidity and mortality of the children of Cambodia.

--Gizelle V. Gopez is a Program Associate for PATH's Cambodia Country Program