Tracking disparities in use of oral rehydration solution to treat childhood diarrhea

Over 500,000 children die due to diarrheal diseases each year despite the fact that diarrhea is a preventable and treatable disease.

One way to prevent diarrheal deaths is through treatment with oral rehydration solution (ORS), a simple therapy made of water, glucose, and electrolytes that was discovered over fifty years ago. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists it as an essential medicine and, together with zinc sulfate, it is the recommended treatment for acute diarrhea. In fact, in July 2019, the World Health Organization added co-packaged ORS and zinc to its essential medicines list for children, harmonizing with diarrhea treatment best practices.

Yet the use of ORS to treat diarrhea remains critically low around the world. UNICEF reported that only 44% of children under the age of five with diarrhea in low- and middle-income countries received ORS in 2017. Many of these are countries where diarrhea mortality rates remain high and a substantial number of deaths could be averted with improved access to this life-saving treatment.

We also know from previous work that progress in scaling up ORS has varied globally, with larger strides made in parts of south Asia compared with the Horn of Africa. But, until recently, we did not have tools to track this variation on a local level.

A new study from our group at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation uses geostatistical models to produce the first estimates of geographic variation in ORS coverage (specifically, the percent of children with diarrhea that received ORS) in low- and middle-income countries. We also developed interactive maps that can be used to explore trends in ORS scale-up from 2000 to 2017 at the national level, as well as at subnational levels such as districts, municipalities, states, and regions.

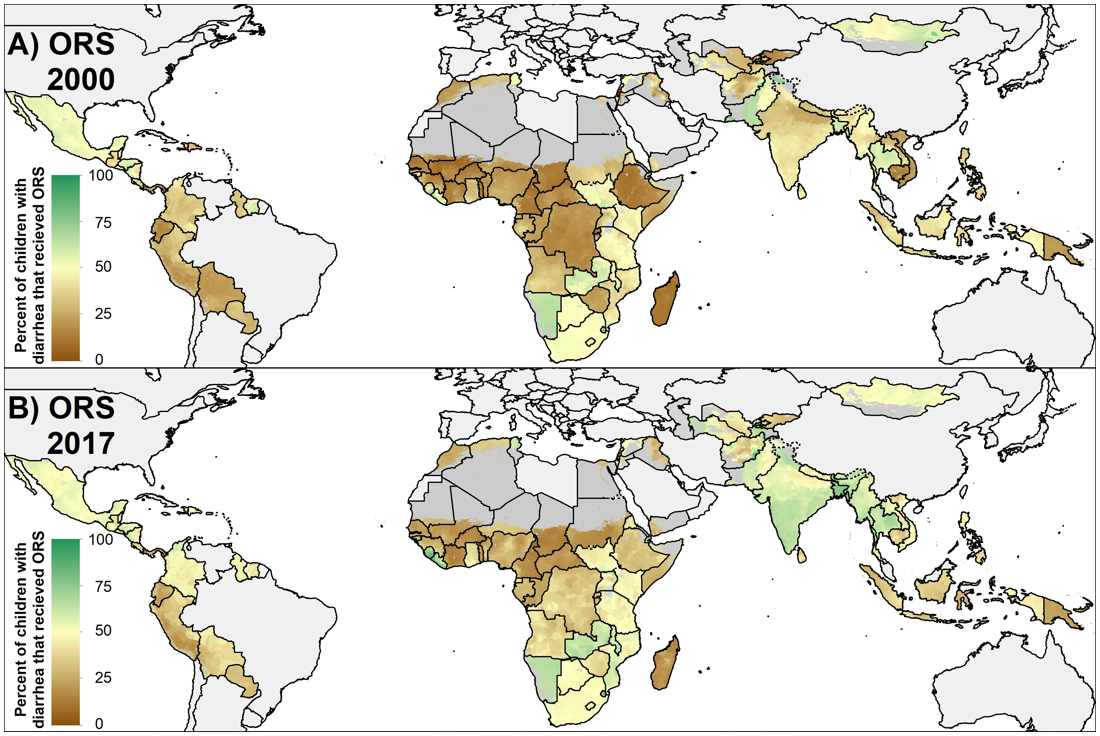

The maps below show that, while ORS uptake has significantly improved in countries such as Rwanda, Vietnam, Bolivia, Cambodia, and India, most countries have seen only incremental progress. In most locations, fewer than 50% of children with diarrhea received ORS treatment in 2017. Importantly, this included 12 of the 14 countries with the highest diarrhea mortality rates.

The maps also show that in some countries, such as Zimbabwe, the use of ORS was fairly evenly distributed throughout the country by 2017. In other countries, large disparities remain. In Peru, for example, average ORS coverage ranged from 16% to 45% depending on the province.

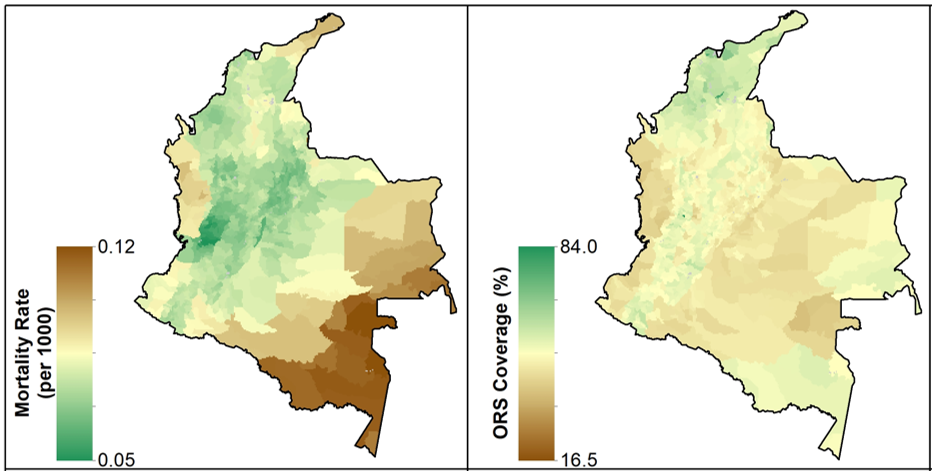

ORS coverage has increased over time between (A) 2000 and (B) 2017, but remains below 50% in most locations. IHMEThe maps show many of the locations where ORS coverage is low are also locations where diarrhea mortality is high. In Colombia, shown below, diarrhea mortality rates are higher-than-average and ORS coverage is lower-than-average in parts of the Amazon and Pacific regions. These may represent areas of increased risk of diarrhea-induced dehydration and death.

ORS coverage has increased over time between (A) 2000 and (B) 2017, but remains below 50% in most locations. IHMEThe maps show many of the locations where ORS coverage is low are also locations where diarrhea mortality is high. In Colombia, shown below, diarrhea mortality rates are higher-than-average and ORS coverage is lower-than-average in parts of the Amazon and Pacific regions. These may represent areas of increased risk of diarrhea-induced dehydration and death.

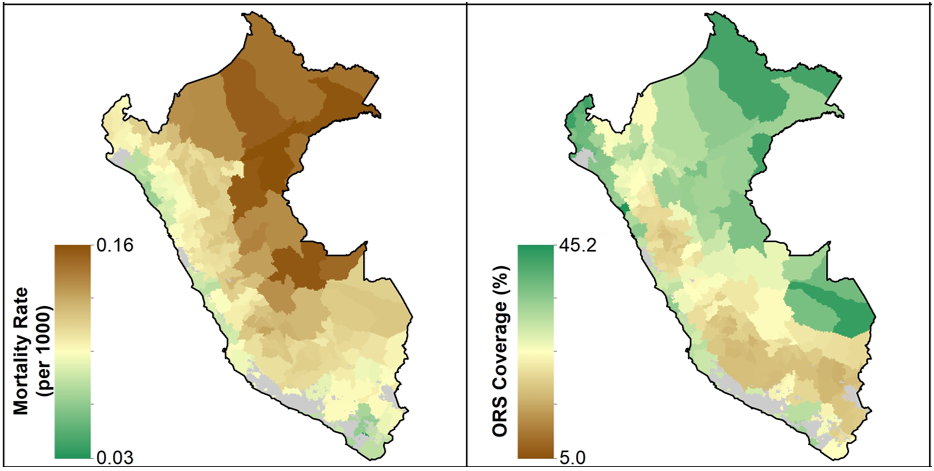

Diarrhea mortality rates are higher-than-average (left), while ORS coverage is lower-than-average (right), in the Amazon and Pacific regions of Colombia. IHMEThere are also countries with the opposite trend. In these countries, ORS coverage is highest in areas where diarrhea mortality is also high. In Peru, shown below, diarrhea mortality is highest in the Amazon Basin region, where ORS coverage is higher-than-average. Diarrhea mortality would likely be even higher in this region if ORS coverage were lower, but there is still room for improvement—maximum ORS coverage in Peru was 45%, compared with 84% in Colombia. It is also important to compare these maps with patterns in other risk factors—such as access to safe water and sanitation, vaccination, and child nutrition—in order to better understand variation in enteric disease vulnerability.

Diarrhea mortality rates are higher-than-average (left), while ORS coverage is lower-than-average (right), in the Amazon and Pacific regions of Colombia. IHMEThere are also countries with the opposite trend. In these countries, ORS coverage is highest in areas where diarrhea mortality is also high. In Peru, shown below, diarrhea mortality is highest in the Amazon Basin region, where ORS coverage is higher-than-average. Diarrhea mortality would likely be even higher in this region if ORS coverage were lower, but there is still room for improvement—maximum ORS coverage in Peru was 45%, compared with 84% in Colombia. It is also important to compare these maps with patterns in other risk factors—such as access to safe water and sanitation, vaccination, and child nutrition—in order to better understand variation in enteric disease vulnerability.

Diarrhea mortality rates are highest in the Amazon Basin region of Peru, where ORS coverage is also highest but remains below 50%. IHMEMuch work remains in scaling up ORS. Improved models and tools such as these maps are an important step towards identifying pockets of the population that are particularly vulnerable to severe dehydration and death. If supplemented with in-depth understanding of local contexts from individuals working on the ground, these new tools could be used to design interventions that improve the health of vulnerable populations. Additionally, new products like the ORS and zinc co-pack can improve access to both ORS and zinc, which has even lower levels of coverage than ORS alone.

Diarrhea mortality rates are highest in the Amazon Basin region of Peru, where ORS coverage is also highest but remains below 50%. IHMEMuch work remains in scaling up ORS. Improved models and tools such as these maps are an important step towards identifying pockets of the population that are particularly vulnerable to severe dehydration and death. If supplemented with in-depth understanding of local contexts from individuals working on the ground, these new tools could be used to design interventions that improve the health of vulnerable populations. Additionally, new products like the ORS and zinc co-pack can improve access to both ORS and zinc, which has even lower levels of coverage than ORS alone.

These continued efforts will be critical to reducing disparities in diarrhea burden and, above all, preventing further unnecessary childhood deaths.