Rotavirus vaccination would save lives in Nigeria—but the poorest may lack access

Photo: A young baby is weighed at a routine visit to Kuje Primary Health Care Center in Kuje, Nigeria. If introduced in Nigeria, rotavirus vaccination would protect Nigerian children from the deadliest form of diarrhea. PATH/Evelyn Hockstein

Of all countries, Nigeria has the second highest number of deaths from rotavirus diarrhea, accounting for 14% of all childhood rotavirus deaths worldwide. In 2016 alone, an estimated 55,474 children under 5 years of age in Nigeria died from rotavirus. A readily available solution, which has worked for over 100 other countries, is rotavirus vaccination. Nigeria has yet to introduce rotavirus vaccination into its national immunization program, but the country has been approved for rotavirus vaccine support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and is currently planning its introduction strategy.

As Nigerian decision-makers were considering how and when to introduce rotavirus vaccines—while continuing to fight COVID-19 and other urgent health threats—a team led by PATH and partners provided support through a rotavirus vaccine cost-effectiveness analysis published in PLOS ONE. Due to the high and persistent burden of rotavirus diarrhea, the analysis confirmed that rotavirus vaccination would be a high-impact and cost-effective strategy for Nigeria. The impact and cost-effectiveness remain high regardless of the specific rotavirus vaccine chosen.

The analysis also uncovered concerning inequities in vaccination coverage. Even though the highest rotavirus burden falls among Nigeria’s lowest-income groups, these populations and geographic areas currently have lower vaccination coverage and are projected to receive only a fraction of the benefit that the vaccines could otherwise provide. Higher-income populations, on the other hand, are both more likely to afford and access the necessary care needed for rotavirus infection and more likely to receive the vaccine—a stark example of the perpetual and cascading impacts of health inequity on vulnerable populations.

To learn more about the analysis and what it means for Nigeria, we asked the lead study author and global health research consultant, John D. Anderson, a few questions. John helped develop this work as a post-doctoral researcher at Appalachian State University.

DefeatDD: What did the analysis reveal about rotavirus vaccine impact and cost-effectiveness in Nigeria?

John: The results support rotavirus vaccination as a cost-effective intervention in all subpopulations across Nigeria. However, we found large disparities in the projected burden, impact and cost-effectiveness of vaccination. These disparities were starkest in the North East and North West regions compared to southern regions, and in the poorest as compared to richer socioeconomic subpopulations in every region.

DefeatDD: Were these findings surprising to you? Why or why not?

John: Yes and no. Though this is the first time publishing the results of this model, we have been working on iterations for several years, initially working with data from 2003. Unfortunately, disparities in Nigeria’s rotavirus burden and access to vaccination have persisted through to our current models of data from 2013, so we were not surprised to find large disparities.

What is surprising is how little the risk factors for rotavirus mortality and access to vaccination have improved from 2003 to 2013 for the poorest subpopulations. I find the slow rate of improvements to be very concerning because these are also the subpopulations that continue to bear the highest burden of rotavirus mortality.

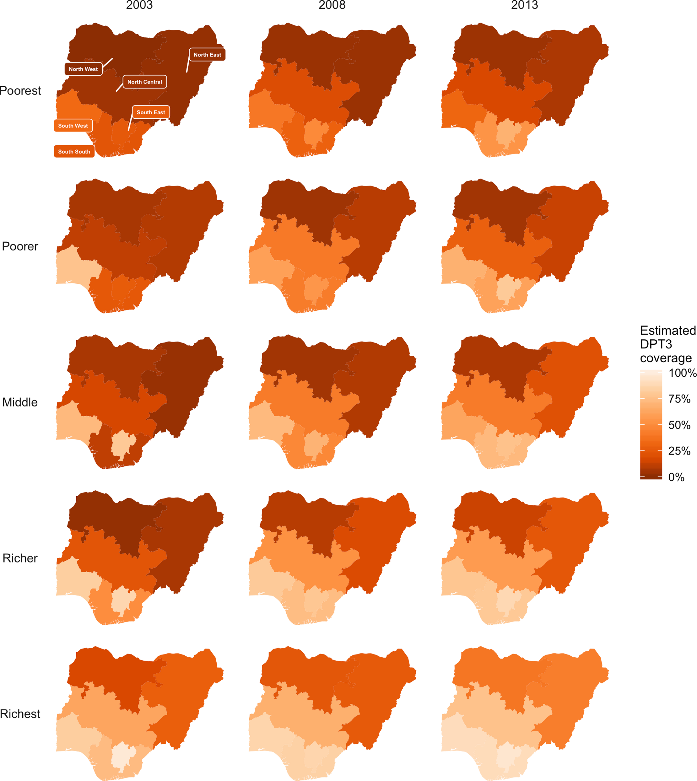

Figure 3 from the cost-effectiveness analysis shows the change in DPT3 vaccination coverage in Nigeria by region and income level from 2003 to 2013. Lower coverage among poorer subpopulations and in the Northern regions is projected to lead to inequitable impact of rotavirus vaccination.DefeatDD: Based on this analysis, what are your recommendations to decision-makers in Nigeria to address disparities in rotavirus vaccination impact and cost-effectiveness?

Figure 3 from the cost-effectiveness analysis shows the change in DPT3 vaccination coverage in Nigeria by region and income level from 2003 to 2013. Lower coverage among poorer subpopulations and in the Northern regions is projected to lead to inequitable impact of rotavirus vaccination.DefeatDD: Based on this analysis, what are your recommendations to decision-makers in Nigeria to address disparities in rotavirus vaccination impact and cost-effectiveness?

John: In Nigeria, where there are roughly 300 different ethnic groups that speak approximately 500 languages, addressing disparities is a very complex problem without a single, overarching answer or policy solution. Our analysis is a first and broad step at locating where and in which subpopulations resources can be allocated in a way that reduces and eliminates disparities.

In Nigeria, where there are roughly 300 different ethnic groups that speak approximately 500 languages, addressing disparities is a very complex problem without a single, overarching answer or policy solution.

With that in mind, our broad recommendations would be to prioritize increasing vaccine delivery capacity to improve coverage in the Northern regions and in the poorest subpopulations across the country. Reductions in disparities in projected vaccination coverage could increase benefits by 149% nationwide and by 350% and 250% in the North West and North East regions, respectively. Efforts would likely need to include a combination of addressing attitudes towards vaccination and the health system, increasing health staff and facilities, and improving vaccine transport and storage capacity.

Additionally, coordinating disease prevention and treatment interventions across multiple sectors—such as nutrition and water and sanitation infrastructure—could significantly reduce disparities in the burden of rotavirus and other forms of diarrhea.

DefeatDD: How might this analysis be helpful for other countries?

John: I think this type of analysis is useful for every country that has not achieved universal vaccination coverage. My colleagues and I have built similar models looking at subnational disparities in rotavirus vaccination impact and cost-effectiveness in other low- and lower-middle-income countries. In all of those cases, we find that prioritizing the most vulnerable and underserved subpopulations is a very effective way to maximize national investments in rotavirus vaccination.