Mini guts, a major breakthrough in norovirus research

Cover photo: Mini guts growing in the laboratory.

Norovirus is the leading cause of gastrointestinal illness across the world—and not to mention one of the most unpleasant. There are an estimated 685 million annual cases of the virus, which leads to rapid vomiting and diarrhea that can be accompanied by influenza-like symptoms. Two hundred million of these cases occur in young children, who are especially vulnerable along with elderly and immunocompromised individuals.

Unlike many other diarrheal diseases, the burden of norovirus is high in both low- and high-income countries. Norovirus causes 200,000 deaths per year, 50,000 of them among children, and accounts for $63 billion in health care costs and lost productivity.

Despite these staggering numbers—and the fact that researchers have known about norovirus for more than half a century—neither preventatives nor therapeutics are available for norovirus. At the end of 2024, World Health Organization identified norovirus as a global priority endemic pathogen, designating that new vaccines for the virus are urgently needed.

Photo credit: Western Washington University.

Why is it so complicated to develop prevention or treatment against norovirus?

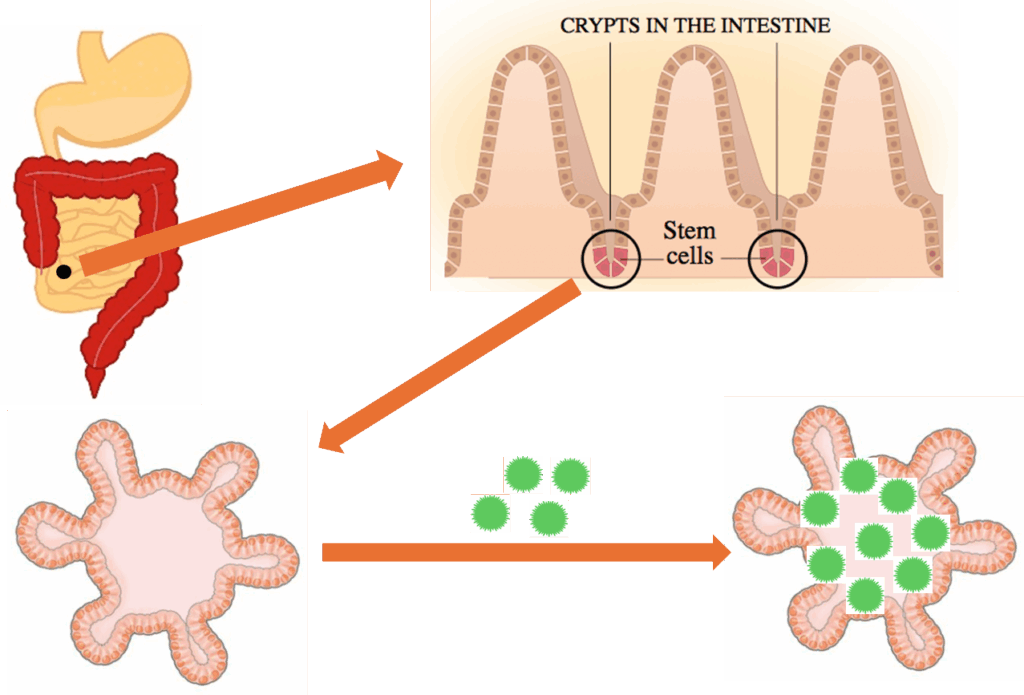

The study of pathogens and their potential interventions depends upon the ability of scientists to grow them in a lab, and for norovirus, finding a growth medium has been a struggle. Enter the era of organoids, made possible by recent advances in stem cell research and demonstrated in 2016 to successfully grow norovirus. Researchers finally have a model for experimenting with antibodies to assess protection and develop interventions.

Human intestinal organoids/enteroids, or, as I like to call them, “mini guts,” are created from a series of biopsies of small intestinal tissue. In the lab under specific conditions, these samples can grow into 3D structures that recreate the intestinal lining of the host. And these structures can be infected with norovirus.

Stem cells derived from human intestinal samples form mini guts in the laboratory. They can be infected with norovirus.

Like a library of fingerprints, these mini guts also have distinct physiological features. This is a major advantage, because noroviruses are genetically diverse, and these similarly diverse mini guts can help researchers understand why certain people are more susceptible to illness than others.

Mini guts aren’t perfect; they are time-consuming and resource-intensive and have limited replication potential. But they represent a groundbreaking evolution in the field. We can now predict protection of some monoclonal antibodies against some noroviruses, advancing our understanding of the immune response. And we can use these insights to identify most vulnerable sites of the virus that can be further employed in the design of protective vaccines. So far, researchers have identified differences in histo-blood group antigen type, bile acid, and innate immune response as factors determining the replication efficiency of norovirus in these mini guts. Time will tell what other major insights these mini guts have in store for us.