If childhood stunting is a three-legged stool, poor gut health is one leg

Dr. Mark Manary, one of the world’s foremost experts in childhood malnutrition, screens children in Chikweo, Malawi. Photo: Carol Lin.

With 155 million stunted children in the world, progress against the complex condition is not coming fast enough to meet the 40 percent reduction target set by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. We spoke to Dr. Mark Manary, a leading expert in childhood malnutrition and professor of pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, to better understand the role of environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) in stunting and potential solutions.

This Q&A was originally published on PATH’s Drug Development blog.

You’re probably best known for the development of ready-to-use therapeutic food, which is the standard of care for severe malnutrition. What inspired your approach and how has that informed your research in stunting?

I believe that if you want to make a big impact, you have to go after a big problem, so I come into a situation asking, “What’s the big problem here?”

In 1994, I was in Malawi on a university exchange and saw that the big problem was children who were sick because they didn’t get enough to eat. With severe acute malnutrition, we’re talking about a significant chance of death within the next month. These kids were unlikely to recover on their own without some kind of help.

We started treating them with standard WHO-recommended methods, keeping children in hospitals and giving them liquid milk. But when we ran into a ceiling of success of 25 to 40 percent, we decided to think out of the box and try home-based therapy. That required a therapeutic food that doesn’t spoil, doesn’t need to be cooked, is easy for mothers to give to their children at home, and is energy dense. That’s how we ended up developing peanut butter-based food. We saw recovery rates up to 95 percent. It was pretty dramatic.

When we were taking care of these children with severe malnutrition, we tested their guts and found they had terrible intestinal barrier function. They were letting all kinds of germs into their bloodstream. I saw my colleagues working on stunting, which is an even more prevalent problem than severe malnutrition, and I realized there could be a link.

What role does environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) play in stunting?

Stunting is the sum of low-grade hits. If you live in a population where you’re having an infection every month, then 25 percent of the time your body does not allow you to grow because it’s prioritizing fighting infection.

Infections like diarrheal disease and malnutrition can feed off of each other in a vicious cycle, as this video shows. Video: PATH.

About one-third of stunting happens before a child is born, one-half between 6 and 15 months of age, and the rest after 15 months of age. I would say that most stunting in utero has to do with infections and inflammation in the mother. From 6 to 10 months of age or so, nutrition is the issue because the child’s diet is really limited. Kids at this age are traveling through a dangerous time. Breast milk isn’t enough, so they’re given watery foods like porridge that aren’t a complete diet.

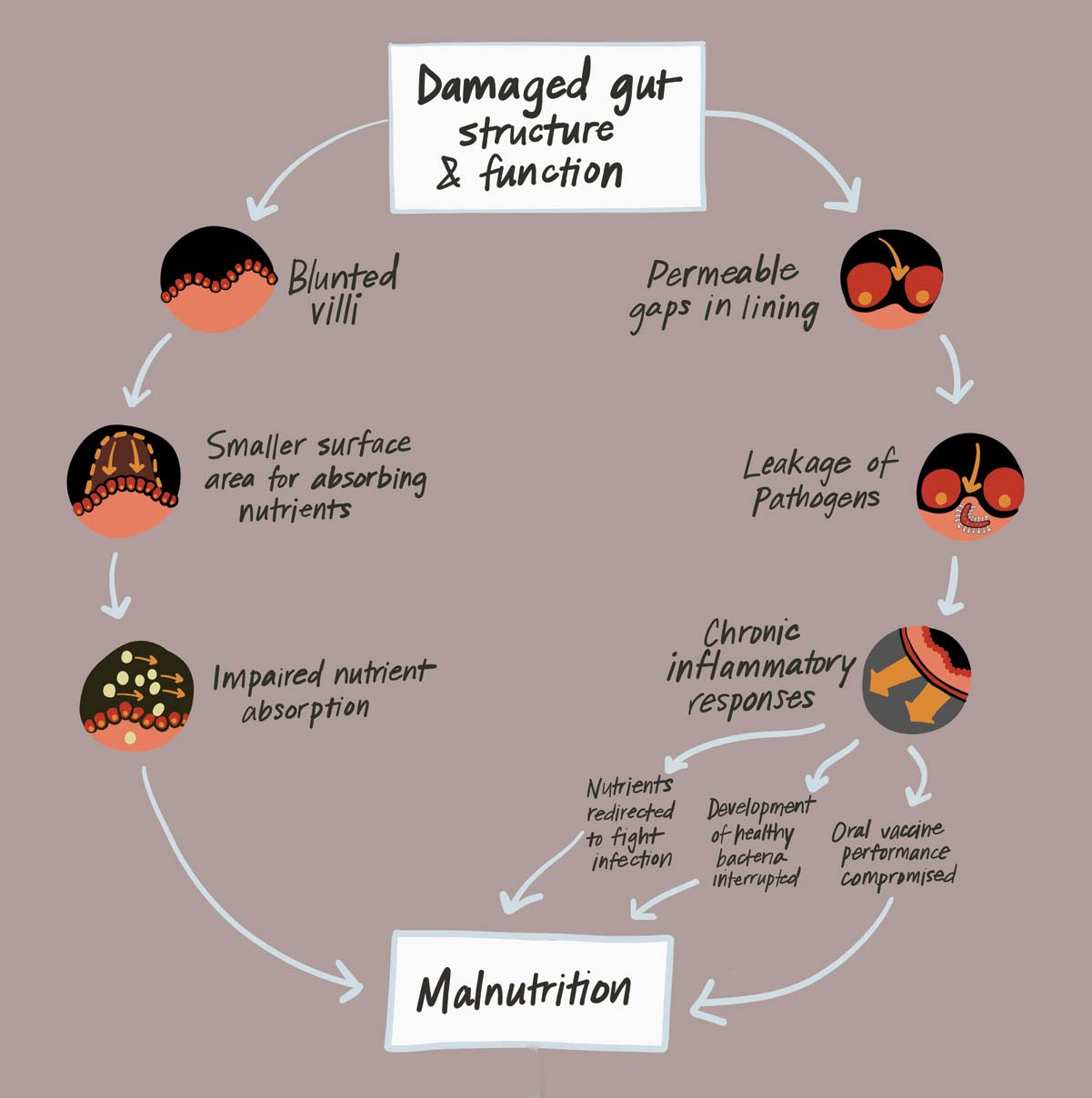

Kids over 10 months old are experiencing environmental exposures. During this time, EED, which is also known as environmental enteropathy, is predominant. EED is a chronic inflammatory state in the gut manifested by gastrointestinal permeability and malabsorption of nutrients.

This generalization assumes a child is breastfed. We observe that children are born short, then they grow normally for six months while they’re breastfed, then growth drops off again. In Malawi, almost 85 percent of kids who had been predominantly breastfed had good gut health at six months. As they diversified their diet and became more mobile, their gut health began to deteriorate.

A Lancet study showed that implementing the best current nutrition interventions would only reduce stunting by an estimated 20 percent. How do you think approaches for stunting need to differ from those for acute malnutrition?

Every time you see a problem as big as stunting, you know it must have many causes. According to Nevin Scrimshaw’s classic cycle of infection, malnourished children are constantly moving in a spiral of poor nutrition, which makes them susceptible to infections, and, as a result, they don’t grow.

There have been tremendous efforts to break that cycle. On the nutrition side, there was the International Lipid-Based Nutrient Supplements (iLiNS) study. Thousands of Malawian children had what nutritionists would say was a perfect diet from the time their mothers were in the middle of pregnancy until 18 months of age, but they did not grow any taller than other children. This was a clue that it’s going to take something more than food.

On the infection side, you can look at interventions against common infections like pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria. When insecticide-treated bednets were introduced in a population of 100,000 people in Kenya, malaria transmission rates fell, but the children didn’t grow any better.

The wrong conclusion would be that neither food nor infection control matter. But it does mean that there’s something else involved.

I think of stunting as a three-legged stool. The stool’s platform is good growth and development. One leg of the stool is diet. The second leg is your exposure to infections. The third is the health of your gut: is your gut performing the barrier functions or does it have EED? It’s going to take a combination of interventions to address the three legs of the stool.

The third leg of growth and development is good gut health, says Dr. Manary. Without it, children can develop environmental enteric dysfunction, which can result in chronic malnutrition and stunting. Image: PATH.

The third leg of growth and development is good gut health, says Dr. Manary. Without it, children can develop environmental enteric dysfunction, which can result in chronic malnutrition and stunting. Image: PATH.

You’ve done more clinical trials on stunting and EED than anyone else. What’s worked and what hasn’t?

We’ve done seven studies now trying to improve gut health. We tried probiotics and antibiotics to displace or kill bacteria in the gut, but neither had an effect. This makes sense because enteropathy is in the small intestines, where we absorb nutrients, whereas most bacteria is in the colon. Deworming, micronutrient supplementation, and zinc had only a small effect.

This litany of failed attempts is a testament to the fact that the problem is that recalcitrant.

The only thing that has had a significant effect on growth is legumes. We’ve just published the results of a study we did in Malawi with two different types—common beans and cowpeas, also known as black-eyed peas. We roasted and ground them into flour, and mothers sprinkled it on their kids’ porridge.

After six months, 6- to 12-month-olds who were given the cowpea supplement had grown more than the controls. This is the first food we’ve found that has helped gut health, so a high-quality protein targeted at the 6- to 12-month-old child seems like a good bet. In addition to providing protein, the legumes have glutamine (a building block for protein), which stimulates the gut barrier function to heal and regenerate.

Children aged 1 to 2 years saw benefits from the cowpeas in terms of gut health. At their age, poor gut health is related to poor sanitation, because they are exposing themselves to a lot more in their environment, like bacteria from animals living in the home. Legumes are also high in fiber, which may have a positive effect on the gut microbiome.

What interventions are you pursuing next?

Until just recently, most people would have said it’s all about sanitation. Two large and impeccable studies—the Sanitation Hygiene Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) trial and WASH Benefits—went after this hygiene hypothesis. The results, which came out recently, were disappointing. Building pit latrines and improving sanitation didn’t reduce EED or improve growth, though provision of nutrition supplements did improve growth by a small but significant increment.

Now that we’ve had some success with legumes, I would like to augment them by reducing child contact with animals. We’re also investigating the effect of milk oligosaccharides, which are compounds in mammal milk that strengthen the biofilms in the gut that may protect epithelial cells and improve barrier function.

We’re doing a trial in Malawi to determine if we can decrease enteropathy with a daily supplement of lactoferrin and lysozyme, enzymes found in breast milk that reduce or kill bacteria. Breastfeeding is so protective. I think that we can enhance gut health by copying some of its natural strategies.

Learn more about environmental enteric disorder and PATH’s work to develop drugs for diarrheal disease.