Diarrheal disease in the climate of the future

Families collect water in a displacement camp outside Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they were forced to flee after a volcanic eruption. Photo: PATH/Ley Uwera.

US scientists have confirmed that a weather event known as El Niño which occurs every two to seven years, is about to form in the Pacific Ocean. This is going to take us into what scientists call the “uncharted territory” of global temperatures. This impending weather event may have a large human and economic cost, especially for refugee populations.

El Niño is a naturally occurring phenomenon that occurs when warmer seawater comes to the surface of the Pacific Ocean. This pushes heat into the atmosphere, which will affect weather all over the world until next spring and could temporarily lead to crossing the 1.5 C threshold (set under the Paris Agreement) of global surface temperature in the next five years. This will result in storms, floods, droughts, wildfires, and other extreme weather events that will cause misery and suffering, especially for the refugee population. It will be worst in the coming winter when it peaks and will have different impacts in different parts of the world, including drought in Australia, heavier rainfalls in the Southern US, and a weakened monsoon season in India. El Niño occurred many times over the last century, but this time it gains strength from the warmth of the sea, which is at record levels. El Niño is coming on top of record-warm temperatures and will further increase global surface temperatures.

This form of climate-fueled temperature rise drives people from their homes and forces them to evacuate, making life even more dangerous for those who have already been displaced due to conflict, persecution, and political insecurity. There are millions of displaced climate refugees in Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the vast semi-arid Sahel region in Africa because of catastrophic flooding. In Afghanistan, Madagascar, and the Horn of Africa, people have had to flee from prolonged droughts.

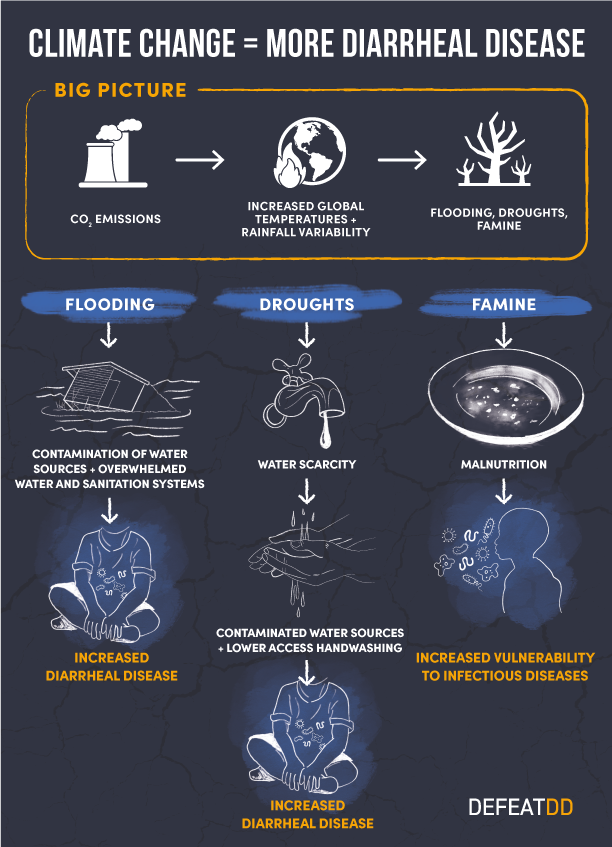

The frequency and intensity of heat waves in different parts of the world due to rising temperatures are exacerbated by El Niño, and such extremes hold implications for diarrheal disease. One study found a relationship between rising temperatures and diarrheal disease in children under three years old, where weather anomalies like precipitation shocks are associated with an increased risk of diarrhea. Also, extended dry or wet periods influence the spread of pathogens, especially in communities that lack essential sanitation infrastructure. Empirical evidence indicates that over 58 percent of known human pathogenic diseases, including cholera, are aggravated by climatic hazards. Another study found an association between every 8% increase in the incidence of diarrheagenic E. coli and a 1°C increase in the mean monthly temperature. WHO estimated that there could be more than 32 thousand additional diarrheal deaths among 0–15-year-old children worldwide in the year 2050 due to climate change.

Its symptoms are already evident. The Horn of Africa is facing one of the worst droughts in nearly four decades. Droughts and tropical storms have affected the availability of clean and safe drinking water in those regions. Cases of cholera outbreaks have been increasing due to drought, floods, and cyclones in South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Mozambique. WHO reported cholera outbreaks in 24 countries through May this year, compared to 15 the previous year. The United Nations estimated that a billion people in 43 countries are at risk of cholera, with children less than five years old being particularly vulnerable.

Such a situation does not bode well for refugees, either. According to UNHCR, since 2008, an average of 21.5 million people have been forcibly displaced by weather-related sudden-onset hazards such as floods, storms, wildfires, and extreme temperatures every year, and these displaced people are at risk of cholera and other diseases. At Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, surveillance data indicated E. coli contamination in groundwater. To solve this, groundwater usage was prohibited, and authorities switched on treated surface water for drinking and took measures to improve the fecal sludge treatment settings in the densely populated camp areas. Also, large-scale oral cholera vaccination campaigns were underway to protect the refugees.

These examples and the forthcoming El Niño remind us of the urgency to invest more in climate-resilient water and sanitation systems and vaccination. Otherwise, cholera outbreaks will not subside, and may well worsen as we confront the climate of the future.