All Available Tools: Integrating Vaccines into Zambia’s Cholera Response

These crowds are a testament to the Government of Zambia’s commitment to social mobilization to raise awareness about the country’s oral cholera vaccine campaign. Photo credit: CIDRZ.

Vibrio cholerae can steal through a community quickly and quietly. This bacteria spreads in water or food, causing acute diarrhea that can cause severe dehydration and death in just a few short hours. But, cholera is both preventable and treatable.

Zambian Minister of Health Chitalu Chilufya has seen first-hand the impact of cholera, and understands the vital role governments must play. As he said in a recent African Center for Disease Control (CDC) board meeting, it is unacceptable that a preventable and treatable disease such as cholera has continued to claim millions of lives worldwide. Dr. Chilufya agreed to sponsor a resolution on the elimination of cholera at the 2018 World Health Assembly – an important step towards global action.

Dr. Chilufya’s passion to eliminate cholera comes from the experience of Zambia itself. On October 6, 2017, Zambia officially declared an outbreak in the capital city, Lusaka. At that time cases were sporadic, but by the end of November, there were more than 300 cases and four deaths.

New boreholes were drilled to give people access to clean sources of water. Handwashing stations appeared outside of people’s homes and in public spaces. You could barely turn around without seeing a poster about using chlorine or boiling water. As a further measure, schools remained closed into January following the holiday break. Community gatherings – markets, churches, weddings, funerals, night clubs – were banned until further notice. Public Health Inspectors visited supermarkets and restaurants in search of V. cholerae. Businesses put in place stricter sanitary and hygiene practices, spraying shopping carts and encouraging customers to wash their hands. By the end of December, the government decided to add yet another strategy: the cholera vaccine.

Data shows the cholera vaccine provides significant protection and can be an effective part of controlling an outbreak. In Zambia, the Ministry of Health brought together a multisectoral team to plan the largest ever oral cholera vaccination (OCV) campaign, targeting 1.2 million people over ten days in January 2018.

For a vaccination campaign to be successful, people must come to get vaccinated and vaccines must be available. Thanks to the ongoing prevention work, cholera was already on people’s minds. Over 600 community volunteers were trained to carry out community social mobilisation. These volunteers went door-to-door in the target communities demonstrating hand hygiene and the use of chlorine to make water safe for household use. Vaccination points were set up in schools, churches, police stations, and other public venues, but even with more than 70 vaccination sites, there was still overcrowding and long wait times in many places.

Logisticians, pharmacists, and Ministry of Health officials were charged with getting vaccines from storage facilities to the vaccination sites. Initially, it was hard to estimate the demand at each site, leaving many without enough vaccines or vaccination cards. Some vaccination sites could only receive daily amounts because they didn’t have the right equipment to store the vaccines overnight. Limited transportation was stretched, causing delays in replenishment. By the end of the second day, it was evident that additional cold boxes, vaccine carriers, and ice packs were needed to meet the demand.

As the campaign progressed, new vaccination sites were added, data verification improved, more cold chain equipment used, and systems of transportation streamlined. By the end of January, 1.3 million adults and children were vaccinated – 108% of the target.

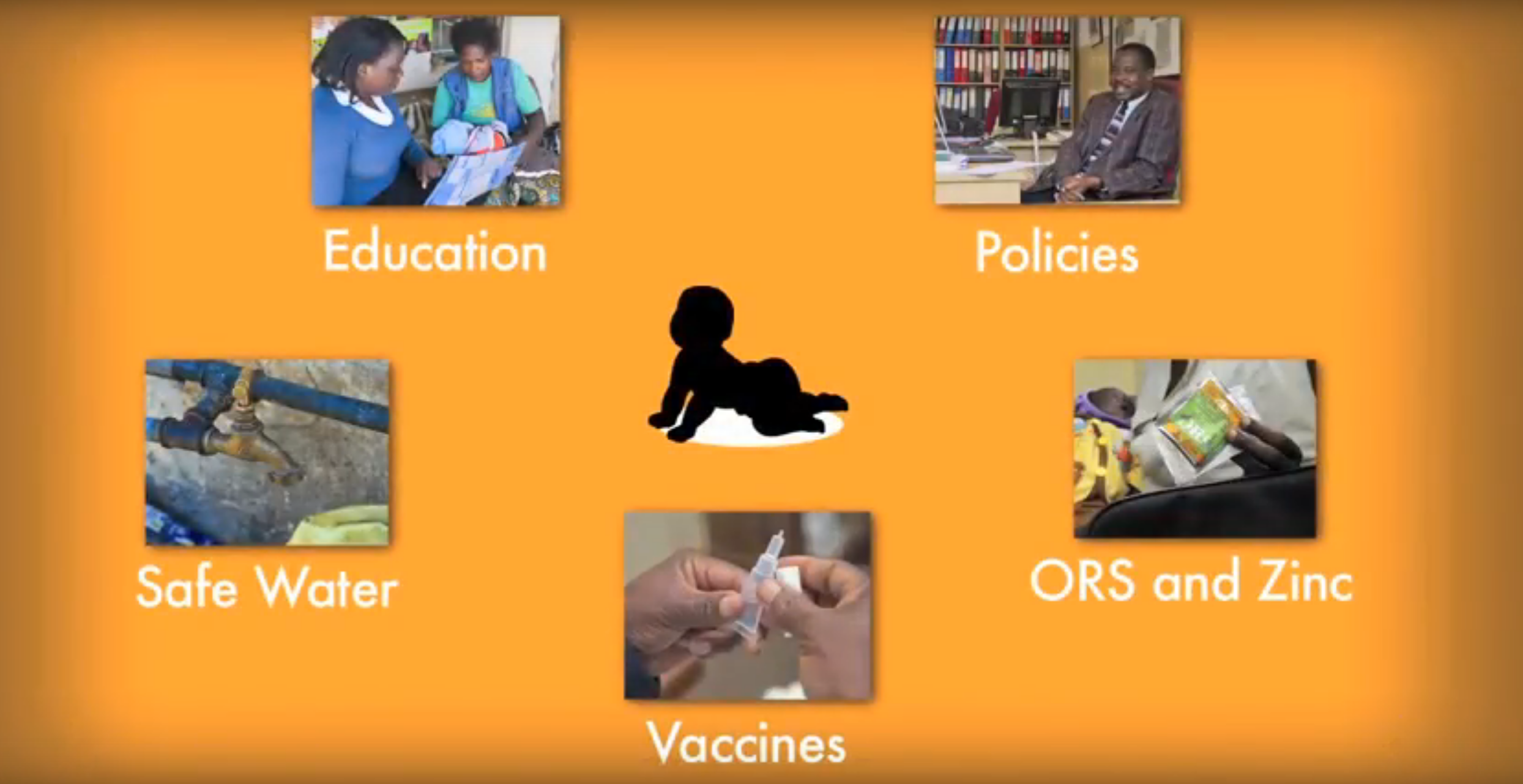

There is a lot to learn from Zambia’s cholera response. The government took a holistic approach, using all of the tools at its disposal to stop the spread of the disease. With so many moving parts, coordination among partners was imperative. Better data and better tools could have helped gauge demand and prevent stockouts. Additional personnel could have eased the burden on the volunteers and health workers at all levels. Establishing transportation routes with adequate transport early could have made deliveries more efficient. With the second round of cholera vaccination underway, these lessons are being incorporated into the campaign. By April 2018, Zambia is expected to deliver more than 2.7 million doses of cholera vaccine.

These challenges from the cholera vaccination campaign are familiar to those of us working to ensure routine immunisations are available to every child in Zambia. While immunisation campaigns and routine vaccinations often operate independent of each other, they rely on the same systems, refrigerators, and people. Strengthening routine systems can provide a strong foundation for disease response, and health officials in the country continue to investigate ways to improve routine immunisation systems. By integrating vaccines into disease response, and incorporating lessons from disease response back into routine systems, we can take a comprehensive approach to improve health systems and stop future outbreaks of dieases like cholera.

Cheryl Rudd is the Deputy Director, Primary Care & Health System Strengthening at Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ). Her work supports Ministry of Health initiatives on vaccine supply chain strengthening in conjunction with partners including VillageReach. Cheryl participated in the planning and execution of the cholera vaccination campaign in 2018.

Video

Video