Simple solution, life-saving potential

|

Many of us have heard the staggering numbers before:

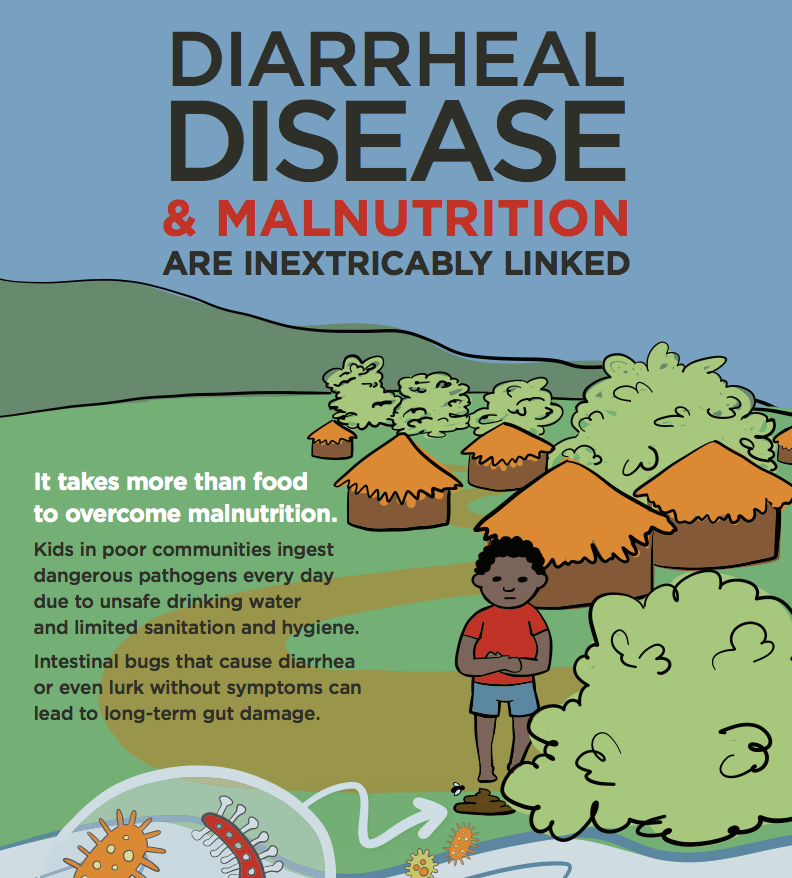

over 880 million people worldwide lack access to safe drinking water; fecally contaminated drinking water contributes to 1.8 million diarrheal disease deaths every year, the majority of which are children in lesser-developed countries. While many solutions to this problem are focused on increasing access to clean drinking water, one solution zeroes in on the simple act of knowing what the quality of one's drinking water is. This was the focus of my recent research at the University of North Carolina's Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Fecal contamination is one of the largest contributors to the contamination of drinking water sources in developing countries. With a lack of sanitation, many people must resort to defecating, bathing, washing, and drinking out of the same water source. In rural areas farm animals, like cows, further exacerbate the problem by defecating and swimming in and around these same water sources. Even in areas where these activities are not taking place directly in a drinking water source, villages up-stream of the source may be contributing to fecal contamination of the water, unknown to those who drink it. It is therefore crucial that individuals have a way to find out about the quality of their drinking water themselves that is affordable, reliable, and simple.

Today, most of our options for determining the quality of a drinking water source require expensive, technical equipment that rely on electricity and access to a laboratory. This type of testing is not appropriate for low-resource settings where the electrical grid is shoddy, if existent, the terrain is too rugged for breakable laboratory equipment and the technical expertise to use it is lacking. A solution that my advisor created and that I worked on for two years to perfect is a simple, portable, low-cost test to determine the quality of a drinking water source. This test manifested in a compartmentalized plastic bag format that uses a color-changing component, which, when dissolved in water will change to a dark greenish-blue color if E. coli (an indicator of fecal contamination) is present.

appropriate for low-resource settings where the electrical grid is shoddy, if existent, the terrain is too rugged for breakable laboratory equipment and the technical expertise to use it is lacking. A solution that my advisor created and that I worked on for two years to perfect is a simple, portable, low-cost test to determine the quality of a drinking water source. This test manifested in a compartmentalized plastic bag format that uses a color-changing component, which, when dissolved in water will change to a dark greenish-blue color if E. coli (an indicator of fecal contamination) is present.

This test, if distributed on a large-scale, would allow an individual, family, or community to take their own initiative in knowing whether their drinking water is contaminated. The color-change component of the test gives a striking result, allowing people to visibly see that their water will make them sick. This is an empowering visual that can be used for educating people about the importance of water quality and to take strides to improve it. While not a perfect solution, this test may persuade a family to use a point-of-use water treatment, like chlorine drops, and therefore help save their children from the burden of diarrheal disease.

-- Katherine Pierson recently completed her M.S.P.H. degree at the University of North Carolina and now works for RTI International in D.C.